❋

Lawful Magic

A tale as old as time.

Three friends strapped on their backpacks and sand-infested Tevas and set out on a two-month journey across Lebanon, Jordan, and Palestine. In the year that followed, the diary entries and photographs collected on this trip made their way into a beautifully designed print book.

The pandemic exposed a complex and overlapping set of emergencies in Lebanon: a collapsing healthcare system, a banking and liquidity crisis, political upheaval, and the catastrophic explosion in the port of Beirut. All proceeds from Lawful Magic were donated to the Lebanon Red Cross to provide food and shelter as the northern winter approached.

Some highlights and excerpts of Tom’s writing can be found below. Photographs by Thom Mitchell. Design by Nick Collins.

Riots swept through Jordan in 1989. The International Monetary Fund had convinced Amman to drop subsidies on fuel, alcohol and – crucially – cigarettes. It’s always the IMF. Unemployment queues stretched. Fuses shortened. For a people denied elections for two decades this was one insult too many. In the south, crowds torched every government building at hand.

One account of how the riots ended, viewed through the vaseline-smeared lens of national history, goes like this: Jordan’s social fabric began to tear, the venerable King Hussein gave a televised speech. His words, at once scolding and reassuring, climbed and climbed. He spoke of love, pride, and duty. He gathered the loose threads, appealing to a sense of identity that sits many strata below nationhood. The rhythm was unmistakable. Hussein embodied the highest expression of Arabic poetry: sirh halal — lawful magic. If we squeeze every last drop out of this analogy: Hussein’s words were the skein that bound together a frayed country. The protests fizzled out.

Another account goes like this: a wily old monarch’s instinct for self-preservation kicked in. He fired the Prime Minister and made some minor democratic concessions in order to please a credulous crowd.

You can choose which one you prefer.

The western slopes of the Lebanon ranges are well serviced by clouds rolling off the Mediterranean. They gather in the valleys and cling to green spurs. Here you’ll find the mighty cedars in damp hollows. But this blanket of stratus infrequently makes it over the crest to nourish the eastern slopes. No, the other side of the mountains are as dry as the proverbial dead dingo. Not that the farmers of the Beqa’a Valley mind. With their modest irrigation channels they grow a truly heroic amount of cannabis and have been doing so for at least a millennium.

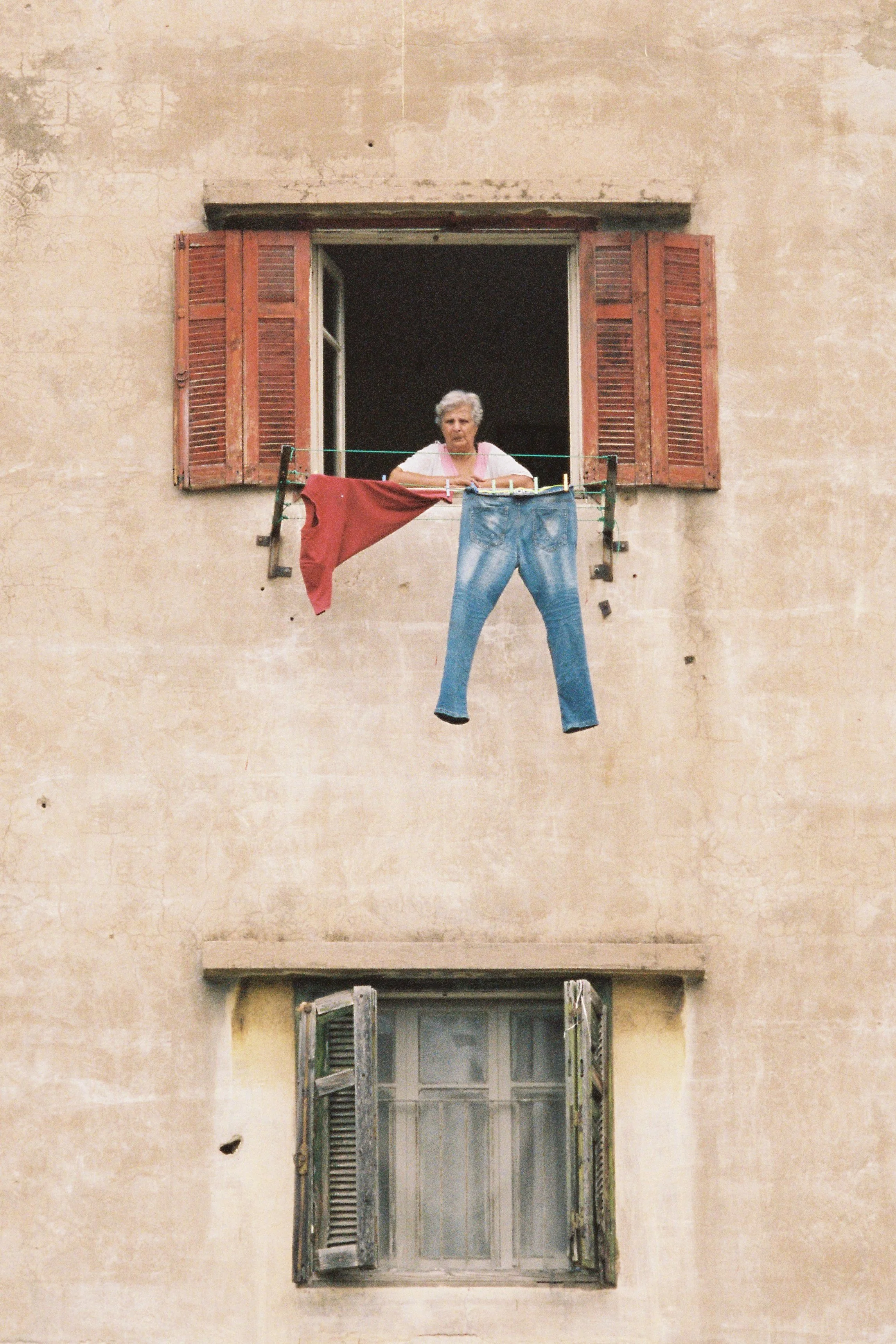

The unofficial and official flags of Lebanon.

Make no bones about it: there are more Brazillian flags in Lebanon than there are Lebanese ones. Despite having objectively the second-best national flag in existence (#1 Kazakh), the Lebanese drape their cars, homes and streets in the green, yellow and starry blue.

All those flags fluttering in the Mediterranean breeze, and in the centre of each one, “Ordem e Progresso”. While “order” isn’t a word that most people would associate with Beirut, “progress” certainly is. Decades of military occupation (by both Israel and Syria) and civil war have left an indelible mark on the capital. It is no wonder that they are more invested in the national projects (read: soccer teams) of Brazil, Argentina, Spain, and Germany. No one seems too worried that their Prime Minister was kidnapped by Saudi Arabia for a hot minute in 2017: Neymar is playing.

It’s June and the World Cup is in full swing. Mo Salah’s one-man Egyptian team has been eliminated so everyone is back onto their European or South American favourites. But the old masters falter one by one until just Croatia and France remain. It’s no great surprise that most of the Arab world turned Croatia devotees overnight. Raymond IV of Toulouse and Godfrey of Bouillon might’ve had something to it.

And then of course there are the other flags: in South Beirut the national flag makes way for the insistent yellow field and green imagery of the Party of God. Before you start clutching at pearls: it’s just a Hezbollah flag – it can’t hurt you.

To find yourself walking the Siq is a rare treasure in this life. A desert crevasse; startlingly deep and narrow. The rose sandstone turns golden where the overhead sun seeps in, but around the bend is subterranean cool and a stale dampness. In heavy morning traffic there is barely enough room for camels (inevitably laden with one doughy Anglo or another) to pass one another.

After a kilometre Al Khazneh (The Treasury) reveals itself. At first, a glance when the serpentine gorge allows it – then in all its majesty. An immensity of hewn rock on the opposite canyon wall looms over you. Bare-chested Amazons wield double-headed axes and minor Olympian figures guard the entrance; mythical Greek icons that nod to the unbelievable span of the Nabatean trading empire. Columns carved straight from the rock announce opulent rooms beyond them, somewhere deep in the cliff. Everything is too large, an exaggeration.

Here in the shadow of the monolith you can make out the eagles on the upper reaches, ready to lift the inhabitants' souls to heaven. This isn’t a treasury after all.

At dusk the wildlife of Jordan reclaims the stretches of desert between the mesas. Mountain goats, desert hedgehogs, a caravan of camels, foxes. All drawn to Wadi Rum’s primary source of nourishment: a bedouin cooking out the back of a chopped up Nissan Patrol.